Friday is the 80th anniversary of Kristallnacht – the Night of Broken Glass. The pogrom of 9 November 1938 in Nazi Germany demonstrated to the Jewish population their lives were in urgent danger and that they must leave if they could. But where to go? Other countries were reluctant to take refugees and adults were finding it increasingly difficult to get out, so Jewish organisations in Germany, Europe and the US attempted to get children out, persuading governments to take child refugees on temporary visas.

Ten thousand came to the UK, on trains and boats organised by Jewish groups and other philanthropic organisations. This week, an exhibition opens at the Jewish Museum in London featuring the stories of six of the children who came to the UK from Germany as part of this rescue effort, which came to be known as the Kindertransport. The six are now in their 80s and 90s, and have made short films recounting their experiences.

I visited each of them in their homes and heard their remarkable, moving, often tragic testimonies. Some never saw their parents again; all suffered the pain of separation; some were so traumatised they couldn’t speak of what had happened to them for decades afterwards – not even to their children. But in each the light of defiance, humour and commitment to life shines through. And each now goes into schools to talk to young people about what they and their parents suffered, testifying both as an act of remembrance towards their parents but also as a warning to the next generation that intolerance, hatred and scapegoating of minorities are ever-present threats.

Bob Kirk, 93, and Ann Kirk, 90: ‘The parents who allowed their children to go showed tremendous courage’

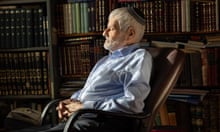

Bob Kirk was given his sharp, pointedly British name by a Scottish captain when he joined the army towards the end of the war. His real name is Rudolf Kirchheimer. Is there any of Rudolf Kirchheimer left? “I suppose there must be somewhere,” he says.

Kirk’s father owned a textile warehouse in Hanover, in northern Germany. In the years before Hitler came to power in 1933, Kirk enjoyed idyllic family outings with his parents, brother and sister, who was 12 years older. His father had won the iron cross in the first world war and was proudly German. He was also close to 60 and reluctant to leave Germany.

Kirk’s sister left Germany in 1936, moving first to South Africa to work. She got married there, and then went to Brazil, where she and her husband lived for the rest of their lives. Kirk only met his sister again in 1981. His brother, who was two years older, went to the UK in February 1939 on a training work permit. His parents then put their remaining child down for a Kindertransport, and he left, just before his 14th birthday, in May 1939.

“I didn’t really know where I was going,” he recalls. “There were about 200 children on that transport, and we were all, to say the least, a bit nervous. You are concerned, excited, and most of us were sold the idea that we were going on an adventure, and that, of course, our parents would be coming as soon as they got their papers.” He was carrying his small regulation suitcase, and had his stamp collection confiscated by Nazis at the Dutch border. He carried no family photos or memorabilia. “My parents were so intent on not making it seem like a parting that they didn’t include anything which might suggest we wouldn’t see each other again.”

As they parted, his parents told him to be a good boy and that they would see him soon. But he never saw them again. Kirk went back to Hanover in 1949 and discovered that they had been transported to Riga in December 1941 and never returned. He also visited his father’s old textile business and found two of his father’s former employees now running it. He recalls them being far from pleased to see him. He would have reclaimed his father’s business if he could, but when he visited his father’s former bank they told him all its old records had been destroyed in the allied bombing.

Kirk says he lost almost 20 family members in the Holocaust. How, I ask him, did he cope with the pain? “With difficulty,” he says. “It’s not something where you say: ‘I’ve got to get over this.’ You just live with it and, eventually, you assimilate it. I never felt guilty about surviving. I felt tremendous gratitude to my parents for their courage. All the parents who allowed their children to go showed tremendous courage.”

After being demobbed from the army, Kirk trained as a bookkeeper and did well, rising to the position of company secretary in a textile company – a neat link with his father’s old line of work. In the late 1940s he met the former Hannah Kuhn (who became Ann Kirk after their marriage in 1950), another Jewish refugee from Germany, who came to the UK on a Kindertransport in April 1939.

The Kirks say they found great solace in being able to talk to each other about their experiences, but they didn’t talk to their sons about what they had been through, wanting them to “have as normal a life as possible and not burden them with our history”. One son did not hear their full stories until they gave a talk at the local synagogue in 1992. Bob refers to “40-year syndrome” – the time it took for Holocaust survivors to start opening up about their lives and for other people to be willing to listen.

Ann, an only child who grew up in Cologne, also lost her parents. Her father was musical and used to play chamber music with friends in their large flat; even now she says she finds music for the cello, her father’s instrument, hard to listen to without weeping. Her parents had a boat, and she says weekend journeys on the Rhine with them are still her “treasured memories, coming back at sunset with a view of the bridge and the cathedral – Cologne was lovely”.

Her recollection of leaving her parents to board the Kindertransport – by this time they had moved to a much smaller flat near Berlin – are deeply affecting. “Everyone around us was in tears,” she recalls, “but my dad tried to joke about it. I was going on a big adventure. What a wonderful chance for a little girl to have. Then they must have jumped into a taxi to get to the next station but one, and there they were waving – waving until their hands almost dropped off, and that’s the last sight I ever had of them.”

She received frequent letters from them before the outbreak of war in September 1939, and then a Red Cross message from her father to her foster family – two middle-aged, unmarried Jewish sisters in Finchley, north London – saying that his wife had been deported in December 1942. The following February, she received a further message saying he was well and healthy, and was pleased to hear that she was progressing well in Britain. She later learned he was deported a few days after that message, and many years later she discovered they had both perished in Auschwitz.

“It’s an additional grief that they didn’t even go together,” she says. “What my poor dad was going through; what they both must have gone through. Thanks to the courage and wisdom of my parents and the goodness of the two ladies who looked after me, I am here. The educational work I do now is in part a memorial to my parents. Their memory lives on and they are not forgotten.” I ask her for their names – Herte and Franz Kuhn. Sometimes names, among the bald, brutal statistics, are necessary.

Remembering the Kindertransport: 80 Years On is at the Jewish Museum, 129-131 Albert Street, London NW1 from 8 November to 10 February www.jewishmuseum.org.uk

Bernd Koschland: ‘It was only as I grew older that it started to hit me hard’