Far more attention should be devoted to preventing mental illness rather than simply treating it as it arises, health experts say, comparing the current approach to only treating heart disease after a cardiac arrest.

At the start of a new Guardian series on illnesses estimated to affect almost a billion people worldwide, leading researchers say money and lives could be saved by investing more in keeping people well.

They say the revolution in personal fitness, diet and medicine over the past 50 years has transformed physical health, but that there have been few similar efforts to keep people well mentally.

“Prevention is much less developed in mental disorders than in other areas of medicine,” said Ron C Kessler, a Harvard Medical School professor. “In psychiatry and psychology it is like we are practising 1950s cardiology, where you wait for a heart attack and once it happens you know what to do.

“We need to go upstream a bit more.”

Mental health is still poorly resourced compared with physical health, and it is decades behind in terms of prevention. Some businesses are grappling with it, with mental health first aiders, digital counsellors and awareness campaigns. Some schools also teach pupils about psychological resilience from a young age, and offer counselling on site. Many individuals practise the kind of mental “workouts” that therapists believe help, but overall only 5% of mental health research funding is spent on investigating prevention.

According to World Health Organization, about one in eight people or 970 million individuals suffered from some sort of mental disorder in 2017, and the numbers seeking treatment are soaring.

“There is no epidemic of mental illness sweeping the world, but there is much more talk about it and more people are being treated,” says Harvey Whiteford, professor of population mental health at the University of Queensland.

The result is that services are being overwhelmed. Only 10 countries, most of them in western Europe, have more than 20 psychiatrists for every 100,000 people. Only five have more than one psychologist for every 1,000 people, and only two – Turkey and Belgium – have more than one mental health nurse for every 1,000 people.

Prevention is quickly becoming the buzzword, but it is a tricky subject because mental ill health is still poorly understood.

“There are things we can do, but we don’t know enough about them and they fall outside the health system,” says Whiteford. “It’s not blood pressure, cholesterol and stopping smoking. The risk factors are child abuse, domestic violence, bullying, genetics.”

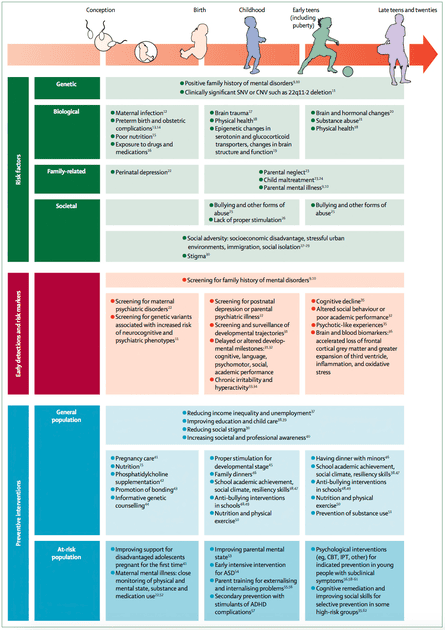

A recent paper in the journal Lancet Psychiatry pinpointed key risk factors that may lead to mental illness. In broad chronological order, they include genetics, early brain trauma, childhood abuse and/or lack of stimulation, bullying, substance abuse, social adversity, shock and trauma, exposure to violence both domestic and military, immigration and social isolation.

The paper produced by researchers in Spain, Australia, the US, Canada and the Netherlands suggested prevention strategies might include:

Policy approaches such as reducing inequality, improving childcare and destigmatising mental illness

Healthcare initiatives such as screening for genetic risks, parental mental illness and delayed developmental milestones in young children

Educational best practice such as tackling bullying, emphasising nutrition and exercise and teaching children to be aware of how they think

Most mental illness first strikes before the age of 25, which leads Ann John, a professor at Swansea university who advises the Welsh government on the prevention of suicide and self-harm, to argue that it would make sense for a lot of prevention work to happen in secondary schools.

She advocates an idea called the “whole school approach”, which is gaining traction in the UK, New Zealand and elsewhere. It emphasises coping skills and resilience, and sees positive mental health as fundamental to the ethos of a school.

Ricardo Araya, a professor at King’s College London, thinks the work needs to start even earlier. He has participated in trials involving pre-teenage children in Britain, Brazil and Chile, helping instil greater psychological flexibility. “We are helping children to understand emotions, normal responses, that what you do will have an impact on how you feel, how to interpret things that happen, how you can poison your own life by coming to the wrong explanation of why things happen.”

He points to the work of the Nobel prize winning economist James Heckman, who has shown that targeted investment in disadvantaged pre-schoolers pays back a 13% annual return through better outcomes in health, social behaviour and employment.

“It has to happen by the age of 10 or you’ve missed the boat in terms of prevention,” Araya says.

Whiteford says that encouraging people to avoid too much stress would reduce their “allostatic load”, an aggregation of psychological trauma that can eventually lead to depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“Everybody has a breaking point,” he says. “We are all on this continuum of vulnerability, and protecting ourselves from psychological trauma is like protecting ourselves from too much exposure to the sun.”

Above all, prevention is about changing the way people think, he says. Shakespeare’s Hamlet says: “There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” It has taken 400 years for people to properly understand what he meant.

“In the physical health world, you are what you eat,” Whiteford said. “In the mental health world, you are what you think.”

Get in touch with your mental health stories and suggestions at mentalhealth@theguardian.com