On Wednesday morning, Adam Schiff, the powerful chair of the House intelligence committee, joined journalists around the world in a nascent Twitter meme: he searched “vaccine” on Facebook and posted a screenshot of the results.

Schiff’s search results were indeed alarming: autofill suggestions for phrases such as “vaccination re-education discussion forum”, a group called “Parents Against Vaccination”, and the page for the National Vaccine Information Center, an official-sounding organization that promotes anti-vaccine propaganda. And while search results on Facebook are personalized to each user, a recent Guardian report found similarly biased results for a brand new account.

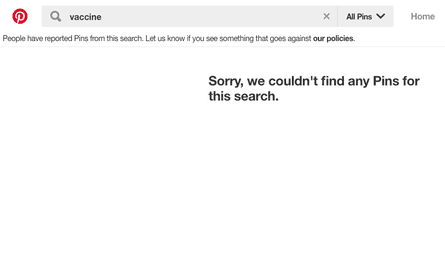

If the congressman had tried to search “vaccines” on the rival social media site Pinterest, however, he would have had little more to screenshot than a blank white screen. Recognizing that search results for a number terms related to vaccines were broken, Pinterest responded by “breaking” its own search tool.

As pressure mounts on Facebook to explain its role in promoting anti-vaccine misinformation, Pinterest offers an example of a dramatically different approach to managing health misinformation on social media.

“We’re a place where people come to find inspiration, and there is nothing inspiring about harmful content, said Ifeoma Ozoma, a public policy and social impact manager at Pinterest. “Our view on this is we’re not the platform for that.”

Last week, I wrote to Facebook and Google to express my concern that their sites are steering users to bad information that discourages vaccinations, undermining public health.

— Adam Schiff (@RepAdamSchiff) February 20, 2019

The search results you get for “vaccines” on Facebook are a dramatic illustration. pic.twitter.com/ZrEQfVTaRo

This hasn’t always been the case. Pinterest, the visual social network, faced scrutiny in 2016 after a scientific study found that 75% of posts related to vaccines were negative. The next year, Pinterest updated its “community guidelines” to explicitly ban “promotion of false cures for terminal or chronic illnesses and anti-vaccination advice” under a broader policy against misinformation that “has immediate and detrimental effects on a pinner’s health or on public safety”.

The policy change cleared the way for Pinterest to deploy a number of technological approaches to combating anti-vaxx propaganda. The company has banned boards by a number of prominent anti-vaccine propagandists, including the National Vaccine Information Center and Larry Cook, who runs the website and Facebook group “Stop Mandatory Vaccination”.

But retroactive enforcement of content rules is just one aspect of the company’s approach.

Take search results. The phenomenon on display in the Facebook search result screenshots is known in technology circles as a “data void”, after a paper by the Data & Society founder and researcher danah boyd. For certain search terms, boyd explains, “the available relevant data is limited, non-existent, or deeply problematic”.

In the case of vaccines, the fact that scientists and doctors are not producing a steady stream of new digital content about settled science has left a void for conspiracy theorists and fraudsters to fill with fear-mongering propaganda and misinformation.

Data voids may be relatively easy to diagnose, but they are very difficult to fix.

“Addressing data voids cannot be achieved by removing problematic content, not only because removal might go against the goals of search engines but also because doing so would not be effective,” boyd wrote. “Without high-quality content to replace removed content, new malicious content can easily surface.”

Pinterest has responded by building a “blacklist” of “polluted” search terms.

“We are doing our best to remove bad content, but we know that there is bad content that we haven’t gotten to yet,” explained Ifeoma Ozoma, a public policy and social impact manager at Pinterest. “We don’t want to surface that with search terms like ‘cancer cure’ or ‘suicide’. We’re hoping that we can move from breaking the site to surfacing only good content. Until then, this is preferable.”

Pinterest also includes health misinformation images in its “hash bank”, preventing users from re-pinning anti-vaxx memes that have already been reported and taken down. (Hashing is a technology that applies a unique digital identifier to images and videos; it has been more widely used to prevent the spread of child abuse images and terrorist content.)

And the company has banned all pins from certain websites.

“If there’s a website that is dedicated in whole to spreading health misinformation, we don’t want that on our platform, so we can block on the URL level,” Ozoma said.

Users simply cannot “pin” a link to StopMandatoryVaccinations.com or the “alternative health” sites Mercola.com, HealthNutNews.com or GreedMedInfo.com; if they try, they receive an error message stating: “Invalid parameters.”

Pinterest is by no means misinformation-free. The Guardian was able to find anti-vaccine propaganda on the site by searching various terms that had not been blacklisted, such as “MMR”, the vaccine against measles, mumps and rubella.

Ozoma said that one challenge was the amount of anti-vaxx material that gets cross-posted from what she describes as “large social media platforms and large video platforms”, rather than from independent websites, because Pinterest doesn’t want to cut off all cross-posting of content hosted by Facebook or YouTube.

“This has not been a focus for other platforms, Ozoma said. ”We’ve been working on this since 2017, but we’ve been kind of alone on it. Hopefully there’s more discussion going forward.”