On a summer day in 2003, a wealthy middle-aged businessman arrived at Karachi airport to board a flight to Bangkok. Saifullah Paracha was heading to the Thai capital to join his American business partner for a meeting with buyers for Kmart, the retail chain.

His wife accompanied him to the airport. The Parachas – Saifullah, Farhat and their four children – lived across town, in the upscale Karachi neighbourhood, Defence. Saifullah’s 14-year-old son, Mustafa, loved gaming, and had asked his father to bring him back a graphics card for his computer from Bangkok.

Saifullah’s eldest son, Uzair, wasn’t there to say goodbye. Earlier that year, the Paracha family had been shocked by the news that Uzair, who was 23, had been arrested by the FBI in New York. Farhat thought that he might have been detained because of the paranoia about Asians, especially Muslims, in the US after 9/11.

A few hours later, Saifullah’s plane landed safely at Bangkok airport – but he never made it to his meeting. Instead, as he left the airport, he was captured in an FBI-led operation. From there, he was transported to Bagram airbase in Afghanistan, where he learned that he was accused of aiding al-Qaida. US authorities claimed that he had, among other activities, facilitated financial transactions for senior al-Qaida members and tried to help them smuggle explosives into the US.

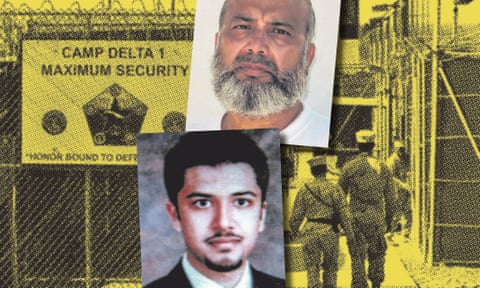

Fifteen years later, Saifullah is still in US custody. He has not been charged with a crime. At 71, he is the oldest prisoner at Guantánamo Bay detention camp, where he has been held since 2004. Saifullah has never had a chance to see the full extent of what he has been accused of, let alone properly defend himself in court. He has not been tried by a military commission, but nor has he been cleared for release by a review board. “There are no charges against him at this time,” a defense department spokesperson told me when asked about charges against Saifullah. “I cannot speculate about the future.”

Guantánamo once held more than 650 men; today, only 40 remain, some of whom have been nicknamed “forever prisoners”. The majority were transferred out or released by successful legal petitions during the Bush and Obama administrations. Nine detainees have died at Guantánamo, including seven from apparent suicide. “Guantánamo has come to symbolise torture, rendition and indefinite detention without charge or trial,” Erika Guevara Rosas, director for the Americas at Amnesty International, said in a statement earlier this year. “Its closure is both essential and long overdue.” Yet Donald Trump, who campaigned on a promise to keep the prison open and “load it up with some bad dudes”, has shut down the state department office charged with negotiating detainee release. The current US policy on Guantánamo, according to Daniel Fried, an Obama-era envoy for the closure of the prison, appears to be: “Keep it as it is, and repeat that these are all dangerous terrorists.”

Over the years, detainees have gone on hunger strike a number of times, with authorities responding by force-feeding them. “Maybe I will lose my sight, and go blind – but in here I have nothing to see,” Ahmed Rabbani, a Pakistani detainee on hunger strike, wrote last year in an op-ed for the Pakistani newspaper Dawn. “We have lost our sanity, our health, our humanity and our dignity,” Shaker Aamer, the last British resident to be held at Guantanamo, said in 2013. Saifullah once described life at Guantánamo as “being alive in your own grave”.

In New York, 1,432 miles away, Saifullah’s son Uzair is serving a 30-year prison sentence on charges of providing material support for terrorism by helping an al-Qaida member. Back in Pakistan, the Paracha family have become pariahs, abandoned by all but a tiny circle of friends and relatives. Yet both father and son insist they are innocent, claiming that they did not realise that the men they were helping were al-Qaida operatives, since they had assumed false identities. In separate interrogations, the alleged al-Qaida members they are accused of helping have said the same thing, claiming that the Parachas had no knowledge of who they were involved with.

For 15 years, Saifullah and Uzair have been held in different spheres of the US justice system, bound by the allegations against them. Guantánamo’s forever prisoners have receded from public consciousness – and even in Pakistan, the Parachas have largely been forgotten, except as a rarely mentioned cautionary tale of how urbane, educated men could be involved in militancy. It is almost as if, having disappeared into US prisons, father and son ceased to exist as anything but a statistic of the war on terror, forever labelled as terrorists. But that convenient narrative ignores one basic question: did they even commit a crime?

In the decades before he was captured, Saifullah Paracha had worked hard to achieve what you might call the Pakistani dream, opening several businesses – including a media production house and a factory that made cement bags – and gaining the trappings of the wealthy: a fancy house, numerous cars, household staff.

Saifullah grew up in poverty in a rural town in newly independent Pakistan. He made his way to Karachi for college, and in 1971, received funding from a youth organisation to study computer science at the New York Institute of Technology, as he told a tribunal at Guantánamo years later. His brother joined him while he was studying in the US.

Although Saifullah didn’t finish his degree, he stayed in the US, and in 1974, he and his brother bought a travel agency called Global Travel Services. Over time, they managed to make a comfortable living for themselves. Saifullah even bought a house in Jamaica Estates – the Queens neighbourhood that was also home to Donald Trump.

In New York, Saifullah met a Pakistani woman called Farhat, who was studying for a master’s degree in sociology at New York University. They married in 1979, and their first son, Uzair, was born in 1980, followed by their daughter, Muneeza. Around that time, Saifullah and Farhat gained permanent US residency, but in 1986, they relocated to Karachi; a relative told me that Saifullah wanted to establish his business in the city, and that he felt happier living in Pakistan. They had two more children, Mustafa and Zahra.

Unlike their father, Saifullah’s children grew up privileged, studying at the city’s best schools. They gained permanent US residency through their parents and regularly travelled to the US. Uzair, the eldest, went to a prestigious Karachi boys’ school, where he was known as a “burger” – 90s slang for westernised, rich Pakistani kids. “He had a goatee when this was considered to be an epitome of a burger kid’s outlook,” one of Uzair’s old schoolmates told me. “I remember he had friends who were girls and maybe a girlfriend. In a middle-class boys’ school, this was an inspiration and achievement!”

While his kids were studying, Saifullah was tending to his many commercial ventures, from his production house that sold original programming to Pakistani media networks, to a garment-buying house with a New York-based partner that facilitated shipments between Pakistan and the US. Saifullah donated to charitable causes and prayed regularly at a mosque affiliated with the prominent cleric Dr Israr Ahmed, who ran the Tanzeem-e-Islami, a conservative religious organisation. He helped build a hospital in his native district in the Punjab province, and chaired a group of small non-profits called the Council of Welfare Organization. His many business and charitable endeavours brought him into contact with Pakistan’s ruling classes – according to his son, Nawaz and Shahbaz Sharif, the ex-prime minister of Pakistan and his influential brother, were among Saifullah’s acquaintances, though it’s possible he exaggerated how well connected he was.

Even though Saifullah was the youngest of nine siblings, over time he became the family patriarch who people turned to for advice and support. He was congenial, generous, high-spirited and a little self-important, cutting the figure of the quintessential Pakistani uncle who loves to talk and talk. When out at a restaurant, he would joke with the staff and give advice to the manager. Saifullah’s businesses had their lean moments, but he was always thinking up new ventures and areas of investment. And in pursuit of new business ideas and networking, he would travel and meet people. It was one of those trips, and a business card, that would change his life beyond belief.

In the 1990s, religious groups in Pakistan would sometimes organise trips to Afghanistan for businessmen, encouraging them to invest there. After the Taliban took power in 1996 – with the backing of Pakistani intelligence – Pakistan was one of only three countries to recognise the new Afghan government as legitimate, and several Pakistani officials and religious leaders had close relationships with Taliban leaders.

Between 1999 and 2001, Saifullah made three trips to Afghanistan, including with religious figures, delegations of businessmen and trustees from the Council of Welfare Organization, which he chaired. The Council’s website listed these trips as “delegations to Afghanistan to promote their economy, which has been shattered and destructed in the last two decades of war”. They are briefly described in the public records of Saifullah’s hearings at Guantánamo over the course of the past 15 years, but offer a confusing picture: the transcripts, particularly from the early years of his detention, consist of vaguely worded, occasionally incomprehensible, questions and answers. In some places, words are redacted or misspelt.

Photograph: AP

What is certain is that on one of these trips, in 1999 or 2000, Saifullah was part of a group of two dozen people who were granted an audience with Osama bin Laden, the al-Qaida leader who was then living in Afghanistan as a guest of the Taliban government. At the time, Bin Laden was wanted by US authorities for funding and organising numerous terrorist attacks, including the 1998 bombings of US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. Yet in Pakistan Bin Laden retained a degree of popularity, particularly among religious conservatives. In 1998, legislators from Pakistan’s Punjab province told US diplomats that Bin Laden had become a folk hero among their constituents after the US ordered a series of airstrikes against him in Afghanistan. But most Pakistani businessmen visiting the country did not get invited to meet Bin Laden, which suggests that Saifullah was indeed well connected.

The meeting with Bin Laden took place in Kandahar. “When I met Osama, he delivered [read] the Qur’an [presumably to the audience in the hall], and said he was a prophet,” Saifullah would later tell a hearing at Guantánamo. “He said nice things, very impressive.”

At the meeting, Saifullah seized the opportunity: he wanted to take advantage of Bin Laden’s celebrity by featuring him in a TV programme, talking about religion as a scholar. “I wanted to make a programme on a common personality between Christian, Judaism, and Islam,” Saifullah later told a Guantánamo review board hearing. “The programme was designed to try and reduce the gap between the international communities and the Muslim community as much as we can,” he said at another hearing. Bin Laden had been interviewed several times before, including in 1997 by CNN, when he answered questions about why he had declared jihad against the US.

In Kandahar, Saifullah handed Bin Laden his business card, but when he returned to Pakistan he didn’t hear back from him. Saifullah returned to Afghanistan the next year, he later told a review board hearing, as part of another delegation that had an audience with Bin Laden. This time, the two did not speak.

In May 2001, with not a little self-importance, Saifullah wrote a five-page letter to George HW Bush, which was copied to George W Bush, in which he laid out the challenges for the Taliban government, asked for sanctions on Afghanistan to be lifted and suggested that the Taliban could help US tackle “communism, terrorism and controlling drugs”.

Later that year, after the September 11 attacks, Saifullah, who was in Pakistan, called his American business partner in New York to check he was safe and to offer his condolences. He also sent his condolences to the US consulate in Karachi. He even wrote a few letters to George W Bush, urging him to pursue peace in Afghanistan.

Then, in the summer of 2002, Saifullah received an unexpected visit at his office in Karachi from a man who had his business card – and claimed to have a message from Afghanistan. According to Saifullah’s testimony at a Guantánamo tribunal in 2016, the visitor, who introduced himself as Mir, wanted to know more about his idea for a TV programme featuring Bin Laden.

The two formed a seemingly casual acquaintance. Mir would come to meet Saifullah at his office, and they sometimes prayed and ate together. Saifullah didn’t make much of the fact that Mir claimed to help with Bin Laden’s media operations – in Pakistan, he would later recall, people often boasted about being close to Osama bin Laden. Perhaps someone more paranoid or cautious would not have entertained Mir, but Saifullah does not seem to have thought much of it. While Pakistan had by then become an ally of the US in the “war on terror”, within the country there was still some support for Bin Laden, as well as for homegrown militant networks fighting against India in the disputed territory of Kashmir.

Over the next few months, Mir asked Saifullah for a few favours, such as helping him open a bank account in Karachi. Mir also gave Saifullah up to $200,000 to hold as a potential investment, which Saifullah returned when asked in November 2002. Mir also introduced Saifullah to a young associate of his named Mustafa, who would occasionally meet Saifullah to discuss technical details about media production, throwing in the odd question about making shipments to the US, though not letting on what he wanted to ship.

Later, Saifullah would say that he had thought Mir and Mustafa – who clearly had a lot of cash at their disposal – might be interested in his latest business venture, Cliftonia, a 330-apartment complex near Karachi’s seafront. Saifullah had committed to invest in the project, which was being developed by a local real estate company, and was looking to raise the finance by finding buyers for the flats.

During this time, Uzair was working at his father’s office in Karachi. While his fellow business school graduates were starting jobs at multinationals and banks, Uzair was planning to travel to New York to market Cliftonia to Pakistani-American expats. When Mir’s associate Mustafa learned that Uzair was heading to the US, he asked for a favour. He had a Pakistani acquaintance, who had come to the US with his family as a teenager in 1996, after his parents were granted asylum. This acquaintance was now living in Karachi and needed help sorting out the paperwork for his US residency status.

Saifullah says he didn’t think much of it: it was his kid helping out another Pakistani Muslim kid – of course Uzair would do it. Shortly before Uzair flew to New York, he and his father met up with Mustafa and the acquaintance who needed help, whose name was Majid Khan, at an ice-cream parlour. Khan gave Uzair a list of tasks: he had to pose as Khan and call the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) on a payphone, as well as close a post office box in Khan’s name, deposit money in his bank accounts, and use his credit cards. The purpose of these tasks, it seems, was both to give the impression that Khan was still in the US, while also helping Khan obtain the documents that would, in fact, enable him to return to the US from Pakistan.

On 17 February 2003, Uzair arrived in New York. During the days, he worked out of the office of his father’s business partner in Manhattan’s garment district; at night, he stayed with relatives in Brooklyn. At the time, Uzair was planning to propose to his girlfriend and had an engagement ring ready.

After Uzair had been in New York for a little while, Khan called him to ask if he’d made any headway. Uzair didn’t have much to report: he hadn’t had much luck getting through to the INS on the phone. He was later able to get through once, but because he didn’t have Majid’s details handy, he only received general information. He did not get round to the other tasks, such as using Khan’s credit cards or depositing money in his accounts.

Then, on 28 March 2003, Uzair was at his desk in Manhattan when agents of the FBI Joint Terrorism Task Force walked into the office. Uzair was taken in for questioning and asked about Khan. At first, Uzair said he was just helping out a business contact of his father. But as the questioning continued into the early hours of the following morning, Uzair changed his story. He said that he knew that Majid Khan was a member of al-Qaida.

On 31 March, Uzair was placed under arrest.

In early March 2003, a few weeks before Uzair was arrested in New York, Saifullah claims he made a startling discovery. Watching TV in Pakistan, he saw a news report about a raid that had recently taken place in the city of Rawalpindi, in which a dishevelled and burly-looking man had been captured by security forces. When Saifullah saw his picture on the TV, he realised that the man he had known as Mir, the man who’d given him the $200,000 to hold, the man who had introduced his associate “Mustafa” to Saifullah, was anything but a potential investor. His real name was Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and, as the alleged architect of the 9/11 attacks, he was one of the world’s most wanted men.

Uzair later told law enforcement agents that Saifullah had phoned him in New York, to tell him what had happened. Uzair asked Saifullah if he should get rid of Khan’s documents – presumably the driving licence and credit cards that were in his possession. Saifullah told him to keep them safe for the time being.

On 5 March 2003, Majid Khan was captured by Pakistani officials in Karachi. While in the custody of the Pakistani government, where he was allegedly tortured, Khan mentioned Uzair and Saifullah Paracha. This information made its way to the CIA site where Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was being interrogated, using torture techniques such as waterboarding, stress positions and sleep deprivation. According to the summary of the US Senate report on CIA torture, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was asked about the Parachas on 24 March 2003, after he had been waterboarded for the 15th time. He said that Saifullah had agreed with his associate Mustafa to use his business as a cover to smuggle explosives into the US. Four days later, Uzair was arrested.

“Mustafa” would turn out to be Khalid Sheikh Mohammed’s nephew Ammar al-Baluchi. After being captured in Pakistan, Baluchi was also transferred to CIA custody, and tortured while under interrogation. But he would deny that the Parachas had anything to do with al-Qaida. According to CIA documents obtained by BuzzFeed earlier this year, Baluchi told US interrogators that Saifullah had “no relation to this business” – that is, no relation to al-Qaida. A document dated 2 May 2003 details an “interview” with Baluchi, where he described talking to Saifullah about media equipment and shipping but without any specifics.

Nonetheless, with Uzair under arrest already, US authorities still wanted to track down Saifullah. On 6 May 2003, the chief of operations for the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center wrote an email to the organisation’s lawyers: “we MUST have paracha arrested without delay and transferred to cia custody for interrogation using enhanced measures. i understand that paracha’s us person status makes this difficult, but this is dynamite and we have to move forward with alacrity. what do you need to do that?” (The unclassified summary of the Senate torture report does not make clear what, exactly, was “dynamite”.)

In late May 2003, Baluchi reaffirmed his earlier claims about the Parachas, claiming that Saifullah was “unwittingly being used”. Baluchi told interrogators that he was using his friendship with Saifullah as part of a plan to attack the US that he was developing with Majid Khan, which required knowledge about how to establish a business in Pakistan, or using Saifullah to do business with a company of Majid’s in the US.

Under further “enhanced” interrogation, Baluchi confirmed Saifullah’s claim that he had only discovered Khalid Sheikh Mohammed’s true identity when he saw reports of the raid. Baluchi described Saifullah as “only a businessman who was sympathetic to the mujahideen” – but also claimed that Saifullah continued to meet with him, as a friend, even after Khalid Sheikh Mohammed’s arrest. Notes from the interrogation state that Baluchi assumed at this point that Saifullah “probably knew [Baluchi’s] al-Qaida affiliation as well”. (To confuse matters further, in his own Guantánamo tribunal hearing four years later, Baluchi denied being a member of al-Qaida.)

Saifullah has insisted that he did not know that any of the men were al-Qaida operatives – though if he did meet Baluchi after Khalid Sheikh Mohammed’s arrest, he was either very naive or very confident he was doing nothing wrong, given that he had been introduced to Baluchi by one of the world’s most wanted men.

It is difficult to know how much of the information obtained through interrogations and torture was actually true. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who remains in Guantánamo, subsequently said that he had lied under torture. Moreover, in the absence of a trial for Saifullah, and given the fact that the available testimony of key witnesses was obtained under torture, it is essentially impossible to make any claim for Saifullah’s innocence or guilt.

In the wake of his son’s arrest in New York, it seems that Saifullah had little idea that he, too, was a wanted man. Instead, he focused on Uzair. “My father was very, very distraught,” Mustafa Paracha, Uzair’s younger brother, recalled. Saifullah wrote to the US ambassador in Pakistan, seeking an appointment to clear his son’s name, though at this stage Uzair had not been charged with a specific crime. According to Mustafa Paracha, his father also spoke to Hamid Gul, the now-deceased former head of Pakistan’s spy agency who wielded influence among Pakistani militant groups and with the Afghan Taliban.

At the same time, Saifullah could not abandon his business commitments. When his business partner in New York asked him to come to Bangkok for a meeting, he went ahead and booked a flight. On 5 July 2003, as Saifullah’s family saw him off at the airport, Mustafa, who was 14 at the time, says he felt apprehensive. “I think he [Saifullah] had the idea that something was about to go wrong, but didn’t really have an idea what,” Mustafa said. As they left the airport, Mustafa had a “weird, impending feeling of doom”.

In Bangkok, as Saifullah left the airport, he was captured by masked men, who hooded him and bundled him into a car. According to his lawyer, Gaillard T Hunt, when Saifullah realised what was happening, “His first thought was: ‘This is an American operation. I’ll be all right.’”

Saifullah was taken to what was most likely a black site in Thailand operated by US intelligence agencies. “They blindfolded him and hung him up on hooks and cut his clothing off,” Hunt said. “He definitely was abused, at the first encounter there in Thailand. But his policy all along was ‘I’m completely innocent, I’ll talk to anybody. No need to use thumbscrews.’”

A few days after his capture, Saifullah was transported from Thailand to Bagram airbase in Afghanistan. A year later, he was transferred to Guantánamo. In 2004, Saifullah had a combatant status review tribunal hearing at Guantánamo, to determine whether or not he could be classified as an “enemy combatant”. If he was found to be an enemy combatant, he would remain at Guantánamo; if not, he would be transferred out.

At Saifullah’s tribunal hearing, a basic summary of unclassified evidence against him was set out. The allegations included that he had met Osama bin Laden twice, supported the Taliban and al-Qaida, been involved in a plan to smuggle explosives into the US, offered media facilities to al-Qaida, taken al-Qaida money for investment, and helped al-Qaida efforts to get hold of chemical and biological weapons.

Saifullah denied the allegations, save for the fact that he had met Bin Laden.

He was declared a combatant.

One key element of the case against Saifullah came from his son, Uzair. When he was first taken in for questioning at FBI offices in New York, Uzair had denied knowing that Majid Khan belonged to al-Qaida, and said he knew nothing about any terror plots. It wasn’t until 4am, after hours of questioning, that Uzair changed tack, telling law enforcement that he “wouldn’t be surprised” if his father were linked to al-Qaida, as Saifullah had met Bin Laden and described him as a “very humble guy”. That night, Uzair agreed to stay at a hotel, accompanied by FBI agents. It was not until the following morning that he was advised of his Miranda rights.

Over the next couple of days, as the questioning continued, Uzair offered more contradictory statements. After having denied he knew that Majid Khan was a member of al-Qaida, for instance, he then said he did know after all. Uzair went back to the night of the meeting at the ice-cream parlour in Karachi. That evening, when Khan had given Uzair a lift on his bike, he had allegedly hinted to Uzair how “good brothers” could help them out.

On 31 March, three days after he had voluntarily agreed to be questioned by law enforcement agents, Uzair was formally placed under arrest as a material witness.

Later, Uzair would claim that he had lied to law enforcement agents. At the time he was first questioned, Uzair was 23 years old and did not have a lawyer by his side. He claimed that his mobile phone was taken from him, he was subjected to a strip search, and that he was threatened with arrest or jail if he tried to invoke his right to a lawyer. (The government denies these accusations.) “I had already told them the truth and I did not go home,” he said at trial. “That is when I started lying.”

Uzair said he’d lied even after his arrest, with his lawyer, a government prosecutor and law enforcement agents present. He’d lied that his father was involved with al-Qaida, and about the alleged transactions and meetings between his father and members of al-Qaida.

In August 2003, Uzair was charged with providing material support to a terrorist organisation and for his assistance to Majid Khan – who, the government said, Uzair knew was an al-Qaida associate. He was held at the notoriously grim Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York for two-and-a-half years before his trial finally began. For most of this time, Uzair says, he was placed in solitary confinement. “About one in 10 guards treated us like human beings. About one in 10 hated us with a passion and terrorised us at every opportunity,” Uzair wrote in a chapter for Hell is a Very Small Place, a book about solitary confinement.

In autumn 2003 Uzair was offered a plea deal: five to eight years in jail if he pleaded guilty. He refused. In December 2003, he was put in an extreme form of solitary confinement, “special administrative measures”. One recent report described these measures as “the darkest corner of the US federal prison system, combining the brutality and isolation of maximum security units with additional restrictions that deny individuals almost any connection to the human world.”

Uzair felt this was a ploy to coerce him into taking the plea deal. His lawyers told him to take it. His relatives, who believed he was innocent, agreed, begging him to take the plea deal. But Uzair was adamant. “Basically, he did istikhara,” said one relative, who wished to remain anonymous, referring to a religious practice where a person prays for guidance. “And the istikhara did not say to take the plea deal. Which, you know … we tried our best.” The relative believes that the cruel treatment Uzair was subjected to made it impossible for him to make rational decisions.

At his trial, which finally began in November 2005, Uzair’s defence rested on the claim that although he did try to help Majid Khan obtain documents to allow him to enter the US, he did not realise that Khan was an al-Qaida terrorist or that he was plotting an attack on the US.

On 23 November 2005, Uzair was found guilty of providing material aid and financial support to al-Qaida terrorists. On 20 July 2006, he was sentenced to 30 years in prison.

Karachi is a city of more than 14 million people, but it can feel like a small, gossipy town, particularly in wealthy neighbourhoods: everyone goes to the same few schools, belongs to the same social clubs and hangs out at the same cafes. As word spread about Uzair and Saifullah, people couldn’t quite fathom the news. After all, the Parachas were a wealthy family who, as far as their acquaintances and relatives knew, were religious but had no links to religious extremism or militant political movements.

“It was shocking,” Uzair’s schoolmate who remembered him as a “burger”, said in an email. “I always thought that if he would do anything bad that would be related to an overdose of booze or drugs which are considered to be the symbols of our liberal elites but it was completely the other way round. Islamic extremism and him??!?”

Although Karachi’s elite rally around some human rights causes, the fate of Guantánamo prisoners is not one of them. In the years after 9/11, many affluent Pakistanis embraced a selective amnesia about the recent past, backing the military regime of General Pervez Musharraf – who claimed to be promoting an “enlightened” and “moderate” Islam – while they turned a blind eye to the rendition of hundreds of men to US authorities and the enforced disappearances of Pakistanis by their own state. Even as homegrown militancy thrived, terrorism was, and is still, seen as a problem that only emerged after September 2001, rather than something that had existed, often with the support of the state, for decades.

The Parachas don’t fit into any of the stereotypes of the other Pakistanis who have been caught up in the war on terror: they’re not poor, nameless men who were mistakenly picked up in a warzone, nor do they seem like fanatical jihadist plotters. Instead, for many Pakistanis, Saifullah looks awkwardly like a typical wealthy businessman – whose meetings and contacts might not have sounded any alarm bells in Pakistan before 9/11.

After all, the Pakistani government dealt with the Taliban and other militant groups, militant leaders regularly appeared in the press, and well-connected businessmen wouldn’t have dreamed they’d be charged for associating with such figures. Saifullah made no secret of his meeting with Bin Laden – his son Mustafa told me that as a kid, before 9/11, he had even told his schoolfriends that his father had met Bin Laden.

With Saifullah at Guantanamo and Uzair in prison in the US, the Paracha family was torn apart. In Pakistan, Saifullah’s many contacts faded away, while relatives refused to come to their house. Uzair’s younger brother Mustafa remembers their attitude as “‘we don’t know you, we don’t want to know you, we don’t care about you, we never knew you’”. Religious organisations that Saifullah had supported now ignored Farhat, Saifullah’s wife, according to his niece.

Farhat was traumatised, recalls Zofeen Ebrahim, a journalist who interviewed her and other members of the family several times from 2006 to 2009. “She told me that she had gone through so much, that she was taking medical counselling, psychiatric help, she was in depression,” Ebrahim said. “But if you look at the family, they were such a normal family like yours or mine would be.”

At the time, the younger Paracha children were still in school, and Farhat and her eldest daughter, Muneeza – who went to the same business school as Uzair – dealt with legal appeals, gave interviews and tried to handle Saifullah’s business affairs. Farhat also worked hard to keep her children on the straight and narrow. When Mustafa “messed up his A-levels tremendously”, as he put it, his mother told him he had to step up. “I made a resolve at that point in time – I’m going to work really, really super hard,” Mustafa told me. “I need to catch up with people studying at Harvard, because I’m going to hold myself to the same standards. My mom worked really hard to keep me in that school, to keep me going in a certain way … ” But there were challenges: a business relationship that went south entangled the family in even more legal and financial problems.

Mustafa and his siblings graduated from university, forged successful careers, and a new family dynamic emerged, revolving around their mother and a close-knit circle of relatives and friends. Around 2017, after years of interviews and court hearings – and seeing nothing come of it – the Parachas mostly stopped speaking to the press. While they continue to support Uzair and Saifullah, in Karachi they will always be seen as “that family” and treated with suspicion or wariness. Earlier this year, they sold their house in Karachi and moved to a new city for a fresh start.

One of Uzair’s fondest memories of his past, back when the Parachas were still a prosperous and well-respected family, were the Eids of his childhood. It was a time when they would get together, a time when Saifullah would preside over dinners and check up on relatives. Those days are long gone.

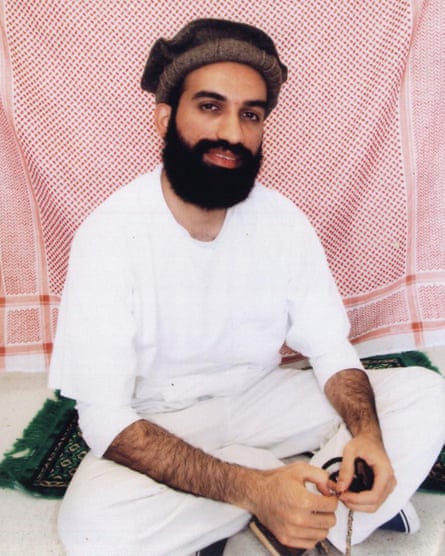

At Guantánamo, the detainees have become a family of sorts and Saifullah has become something like an elderly uncle, who detainees call “chacha” (the Urdu word for uncle). He has taught informal business classes, advising detainees on the kinds of businesses they could develop after they were released. Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, his current lawyer from the non-profit Reprieve, describes Saifullah as a prolific letter-writer who communicates with prison authorities on detainee issues.

Every month, Saifullah has a video call with his family, arranged by the International Committee of the Red Cross. They’re only allowed to share family news, and talk about things such as marriages, births, graduations and deaths. In the years Saifullah has been held at Guantánamo, three of his siblings have passed away. Saifullah tells his family he is well, and even makes the occasional joke, referring to Gitmo as “shitmo”. Even without access to the internet, he likes to stay up to date with the world. When Mustafa mentioned he was interested in renewable energy, Saifullah said he’d read a whole case study on the subject.

Periodic review-board tribunals – instituted by the Obama administration to review detainee cases and recommend further detention or transfer – have denied Saifullah release. On 25 September 2018, the review board ruled that detaining Saifullah remained necessary to protect against “a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States”. The statement said the factors that contributed to the board’s determination included his past involvement and interaction with al-Qaida members.

“The detainee statements regarding his mindset and potential for re-engagement are not credible in light of his continued minimization of his interactions with Al Qaeda, the change in justification for engaging with Al Qaeda, failure to exhibit any remorse for the actions he does acknowledge, and dishonesty in his responses to Board questions,” the statement read.

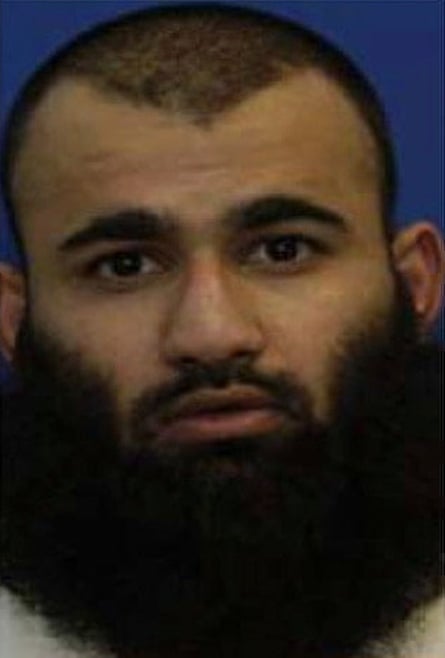

In the years since he was convicted, Uzair has lost hair and gained weight. He is now 38 years old, and his incarceration and solitary confinement have left him with deteriorating eyesight and claustrophobia. He served time at ADX Florence in Colorado – one of the US’s most notorious high-security prisons – and then at Terre Haute in Indiana.

Uzair approached his incarceration as a way of learning. He memorised the Qur’an, he studied Arabic, he read every Islamic book in the prison library – by his estimate, over 50,000 pages on everything from Islamic jurisprudence to Qur’anic sciences. He used to read the Economist, but hasn’t for a while, and occasionally gets copies of the Pakistani newspaper Dawn. Last year, he self-published a book called Secular Stagnation – an account of US economic history that explores the causes of the recession. “I am deeply grateful for the blessings that allowed it all to come to fruition,” he wrote in the acknowledgments, “so much of it was due to opportunities far beyond my control.”

Uzair says he does not regret his decision to turn down the plea deal. “Sometimes the loss is hard to bear but other times I have to remind myself that this was God’s will and I benefited a lot from my time in prison,” Uzair wrote to me recently. The experience of incarceration, Uzair says, has “been a lesson in humility, patience, reliance on Allah, and other important lessons in life.” To his family, Uzair comes across as particularly devout. He once argued with his younger sister over the phone about her adulation of the poet Rumi, who Uzair called a heretic.

“I am not sure I would enjoy the company of my younger self,” he wrote. “I have changed a lot.”

Fifteen years after Saifullah and Uzair were captured, their cases remain murky. Was Saifullah a devious financier, who, along with his son, knowingly helped terrorists who were planning to attack the US, or were they merely pawns in a plot they knew nothing about? Should Saifullah’s interaction with Bin Laden before 2001, and his dealings with a man that he knew was connected to Bin Laden, be seen as a sign of obvious guilt, or simply business meetings that many conservative Pakistanis wouldn’t have been alarmed by? The full extent of evidence against Saifullah is still classified, and Saifullah’s case in the US about the legality of his detention is still ongoing.

The Parachas have continued to insist on their innocence. Their claim, that they didn’t knowingly or deliberately provide assistance to al-Qaida, has become stronger with time, as more details have emerged in additional declassified documents as well as in the Senate torture report and previously unseen transcripts of tribunal hearings from Guantánamo. (In 2012, in exchange for a reduced sentence, Majid Khan pleaded guilty to war crimes, including working with al-Qaida and helping to plot terrorist attacks in the US. Ammar al-Baluchi is still in Guantánamo, awaiting trial.)

In a stunning reversal this summer, a US federal judge ruled that Uzair’s conviction should be thrown out, and granted him a new trial based on evidence that has emerged since he was convicted. That evidence includes newly declassified statements from Ammar al-Baluchi, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and Majid Khan. These statements throw doubt on the claim, made by the prosecution in the original case, that Uzair knew he was helping an al-Qaida member. In his statement granting the motion, the judge wrote: “The Court concludes that the newly discovered material evidence would yield a fundamentally different trial and likely create a reasonable doubt” about Uzair’s guilt.

Ramzi Kassem, a professor of law at the City University of New York who has handled terrorism cases as a defence attorney, told me: “The ruling in the Paracha case isn’t just an indictment of the endemic lack of transparency at Guantánamo and in its military commissions, which potentially cost Mr Paracha many years in prison. It also calls into question the integrity of post-9/11 terrorism trials in US courts more broadly. History will judge most of these cases harshly, in part because defendants are often denied exculpatory evidence on purported security grounds.”

Uzair is again being held at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York, and was initially briefly held in solitary, back where he started all those years ago. In a filing in November countering Uzair’s motion for bail, attorneys for the Southern District of New York cited Majid Khan’s guilty plea to make the case that Uzair knew of his identity and that the government believes it has as strong a case as it did at the initial trial. James Margolin, a spokesperson for the US attorney’s office, declined to comment on whether the government would appeal the ruling for a new trial.

While Uzair will likely have another chance to convince a jury that he is innocent, the only way Saifullah can be released is if he is cleared by a periodic review board, or through a successful habeas petition in the US courts. Neither of those seem likely, and after years of optimism, Saifullah is losing his spirit. “The last couple of times he’s seemed more worried; earlier he’d be joking a lot,” says Saifullah’s niece, Riffat. His physical health is also deteriorating. Saifullah has a history of cardiac problems, as well as diabetes and psoriasis. He told his current lawyer that he was taken to intensive care twice last September. It seems increasingly likely that he will die at Guantánamo.

In Pakistan, Saifullah’s health or continued detention has not made him a cause célèbre. There are five Pakistani citizens detained at Guantánamo, including Ammar al-Baluchi and Majid Khan, but they find little mention in public or political discourse.

“They [the detainees at Guantánamo] have been detained as the ‘worst of the worst’,” says Farhatullah Babar, a former senator from the late Benazir Bhutto’s Pakistan Peoples party, referencing a phrase from former US vice-president Dick Cheney. “I would say they are the wretched of the wretched. And nobody is bothered about the wretched of the wretched people.”