One of the great paradoxes of digital life – understood and exploited by the tech giants – is that we never do what we say. Poll after poll in the past few years has found that people are worried about online privacy and do not trust big tech firms with their data. But they carry on clicking and sharing and posting, preferring speed and convenience above all else. Last year was Silicon Valley’s annus horribilis: a year of bots, Russian meddling, sexism, monopolistic practice and tax-minimising. But I think 2018 might be worse still: the year of the neo-luddite, when anti-tech words turn into deeds.

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

The caricature of machine-wrecking mobs doesn’t capture our new approach to tech. A better phrase is what the writer Blake Snow has called “reformed luddism”: a society that views tech with a sceptical eye, noting the benefits while recognising that it causes problems, too. And more importantly, thinks that something can be done about it.

One expression of reformed luddism is already causing a headache for the tech titans. Facebook and Google are essentially huge advertising firms. Ad-blocking software is their kryptonite. Yet millions of people downloaded these plug-ins to stop ads chasing them across the web last year, and their use has been growing (on desktops at least) close to 20% each year, indiscriminately hitting smaller publishers, too.

More significantly, the whole of society seems to have woken up to the fact there is a psychological cost to constant checking, swiping and staring. A growing number of my friends now have “no phone” times, don’t instantly sign into the cafe wifi, or have weekends away without their computers. This behaviour is no longer confined to intellectuals and academics, part of some clever critique of modernity. Every single parent I know frets about “screen time”, and most are engaged in a struggle with a toddler over how much iPad is allowed. The alternative is “slow living” or “slow tech”. “Want to become a slow-tech family?” writes Janell Burley Hoffmann, one of its proponents. “Wait! Just wait – in line, at the doctor’s, for the bus, at the school pickup – just sit and wait.” Turning what used to be ordinary behaviour into a “movement” is a very modern way to go about it. But it’s probably necessary.

I would add to this the ever-growing craze for yoga, meditation, reiki and all those other things that promise inner peace and meaning – except for the fact all the techies do it, too. Maybe that’s why they do it. Either way, there is a palpable demand for anything that involves less tech, a fetish for back-to-basics. Innocent Drinks have held two “Unplugged Festivals”, offering the chance of “switching off for the weekend ... No wifi, no 3G, no traditional electricity”. Others take off-grid living much further. There has been an uptick in “back to the land” movements: communes and self-sustaining communities that prefer the low-tech life. According to the Intentional Community Directory, which measures the spread of alternative lifestyles, 300 eco-villages were founded in the first 10 months of 2016, the most since the 1970s. I spent some time in 2016 living in an off-grid community where no one seemed to suffer mobile phone separation anxiety. No one was frantically checking if their last tweet went viral and we all felt better for it.

Even insiders are starting to wonder what monsters they’ve unleashed. Former Google “design ethicist” Tristan Harris recently founded the nonprofit organisation Time Well Spent in order to push back against what he calls a “digital attention crisis” of our hijacked minds. Most of the tech conferences I’m invited to these days include this sort of introspection: is it all going too far? Are we really the good guys?

That tech firms are responding is proof they see this is a serious threat: many more are building in extra parental controls, and Facebook admitted last year that too much time on their site was bad for your health, and promised to do something. Apple investors recently wrote to the company, suggesting the company do more to “ensure that young consumers are using your products in an optimal manner” – a bleak word combination to describe phone-addled children, but still.

It’s worth reflecting what a radical change all this is. That economic growth isn’t everything, that tech means harm as well as good – this is not the escape velocity, you-can’t-stop-progress thinking that has colonised our minds in the past decade. Serious writers now say things that would have been unthinkable until last year: even the FT calls for more regulation and the Economist asks if social media is bad for democracy.

This reformed luddism does not however mean the end of good, old-fashioned machine-smashing. The original luddites did not dislike machines per se, rather what they were doing to their livelihoods and way of life. It’s hard not to see the anti-Uber protests in a similar light. Over the past couple of years, there have been something approaching anti-Uber riots in Paris; in Hyderabad, India, drivers took to the streets to vent their rage against unmet promises of lucrative salaries; angry taxi drivers blocked roads last year across Croatia, Hungary and Poland. In Colombia, there were clashes with police, while two Uber vehicles were torched in Johannesburg and 30 metered taxi drivers arrested.

Imagine what might happen when driverless cars turn up. The chancellor has recently bet on them, promising investment and encouraging real road testing; he wants autonomous vehicles on our streets by 2021. The industry will create lots of new and very well-paid jobs, especially in robotics, machine learning and engineering. For people with the right qualifications, that’s great. And for the existing lorry and taxi drivers? There will still be some jobs, since even Google tech won’t be able to handle Swindon’s magic roundabout for a while. But we will need far fewer of them. A handful might retrain, and claw their way up to the winner’s table. I am told repeatedly in the tech startup bubble that unemployed truckers in their 50s should retrain as web developers and machine-learning specialists, which is a convenient self-delusion. Far more likely is that, as the tech-savvy do better than ever, many truckers or taxi drivers without the necessary skills will drift off to more precarious, piecemeal, low-paid work.

Does anyone seriously think that drivers will passively let this happen, consoled that their great-grandchildren may be richer and less likely to die in a car crash? And what about when Donald Trump’s promised jobs don’t rematerialise, because of automation rather than offshoring and immigration? Given the endless articles outlining how “robots are coming for your jobs”, it would be extremely odd if people didn’t blame the robots, and take it out on them, too.

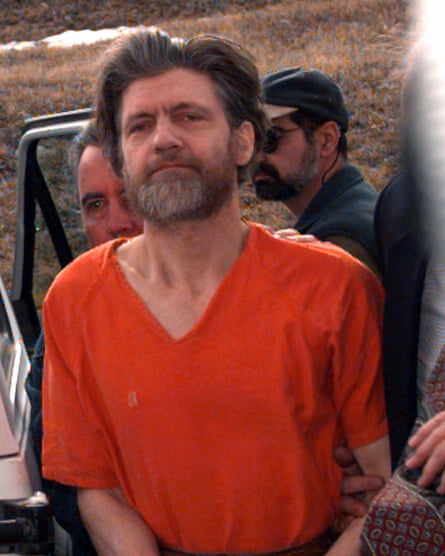

Once people start believing that machines are a force of oppression rather than liberation, there will be no stopping it. Between 1978 and 1995, the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, sent 16 bombs to targets including universities and airlines, killing three people and injuring 23. Kaczynski, a Harvard maths prodigy who began to live off-grid in his 20s, was motivated by a belief that technological change was destroying human civilisation, ushering in a period of dehumanised tyranny and control. Once you get past Kaczynski’s casual racism and calls for violent revolution, his writings on digital technology now seem uncomfortably prescient. He predicted super-intelligent machines dictating society, the psychological ill-effects of tech-reliance and the prospect of obscene inequality as an elite of techno-savvies run the world.

The American philosopher John Zerzan is considered the intellectual heavyweight for the anarcho-primitivist movement, whose adherents believe that technology enslaves us. They aren’t violent, but boy do they do hate tech. During the Unabomber’s trial, Zerzan became a confidant to Kaczynski, offering support for his ideas while condemning his actions. Zerzan is finding himself invited to speak at many more events, and the magazine he edits has seen a boost in sales. “Something’s going on,” he tells me – by phone, ironically. “The negative of technology is now taken as a given.” I ask if he could forsee the emergence of another Unabomber. “I think it’s inevitable,” he says. “As things get worse, you’re not going to stop it any other way,” although he adds that he hopes it doesn’t involve violence against people.

There are signs that full-blown neo-luddism is already here. In November last year, La Casemate, a tech “fab lab” based in Grenoble, France, was vandalised and burned. The attackers called it “a notoriously harmful institution by its diffusion of digital culture”. The previous year, a similar place in Nantes was targeted. Aside from an isolated incident in Mexico in 2011, this is, as far as I can tell, the first case since the Unabomber of an act of violence targeting technology explicitly as technology, rather than just a proxy for some other problem. The French attackers’ communique was published by the environmentalist/anarchist journal Earth First! and explained how the internet’s promise of liberation for anticapitalists has evaporated amid more surveillance, more control, more capitalism. “Tonight, we burned the Casemate,” it concludes. “Tomorrow, it will be something else, and our lives will be too short, in prison or in free air, because everything we hate can burn.”

If the recent speculation about jobs and AI is even close to being correct, then fairly soon “luddite” will join far-right and Islamist on the list of government-defined extremisms. Perhaps anti-tech movements will even qualify for the anti-radicalisation Prevent programme.

No one wants machines smashed or letter bombs. The wreckers failed 200 years ago and will fail again now. But a little luddism in our lives won’t hurt. The realisation that technological change isn’t always beneficial nor inevitable is long overdue, and that doesn’t mean jettisoning all the joys associated with modern technology. You’re not a fogey for thinking there are times where being disconnected is good for you. You’re just not a machine.

Radicals: Outsiders Changing the World by Jamie Bartlett is published by William Heinemann. To order a copy for £17 (RRP £20) go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99

Radicals: Outsiders Changing the World by Jamie Bartlett is published by William Heinemann. To order a copy for £17 (RRP £20) go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion